Architectural Cad Details

Free Architectural CAD drawings, CAD blocks and CAD details for download in the dwg format for use with AutoCAD and other 2D and 3D design software. Browse the list of Architectural AutoCAD detail files available for free download.

18th century axonometric plan,. An architectural drawing or architect's drawing is a of a building (or building project) that falls within the definition of. Architectural drawings are used by and others for a number of purposes: to develop a design idea into a coherent proposal, to communicate ideas and concepts, to convince clients of the merits of a design, to enable a to construct it, as a record of the completed work, and to make a record of a building that already exists. Architectural drawings are made according to a set of, which include particular views (floor plan, section etc.), sheet sizes, units of measurement and scales, annotation and cross referencing. Conventionally, drawings were made in ink on paper or a similar material, and any copies required had to be laboriously made by hand. The twentieth century saw a shift to drawing on tracing paper, so that mechanical copies could be run off efficiently.

The development of the had a major impact on the methods used to design and create technical drawings, making manual drawing almost obsolete, and opening up new possibilities of form using organic shapes and complex geometry. Today the vast majority of drawings are created using software. Main articles:, and The size of drawings reflects the materials available and the size that is convenient to transport – rolled up or folded, laid out on a table, or pinned up on a wall. Sonora matancera. The draughting process may impose limitations on the size that is realistically workable. Sizes are determined by a consistent system, according to local usage. Normally the largest used in modern architectural practice is ISO A0 (841 mm × 1,189 mm or 33.1 in × 46.8 in) or in the USA Arch E (762 mm × 1,067 mm or 30 in × 42 in) or Large E size (915 mm × 1,220 mm or 36 in × 48 in). Architectural drawings are drawn to scale, so that relative sizes are correctly represented.

The scale is chosen both to ensure the whole building will fit on the chosen sheet size, and to show the required amount of detail. At the scale of one eighth of an inch to one foot (1:96) or the metric equivalent 1 to 100, walls are typically shown as simple outlines corresponding to the overall thickness. At a larger scale, half an inch to one foot (1:24) or the nearest common metric equivalent 1 to 20, the layers of different materials that make up the wall construction are shown. Construction details are drawn to a larger scale, in some cases full size (1 to 1 scale). Scale drawings enable dimensions to be 'read' off the drawing, i.e. Measured directly.

Scales (feet and inches) are equally readable using an ordinary ruler. On a one-eighth inch to one foot scale drawing, the one-eighth divisions on the ruler can be read off as feet. Architects normally use a with different scales marked on each edge. A third method, used by builders in estimating, is to measure directly off the drawing and multiply by the scale factor. Dimensions can be measured off drawings made on a stable medium such as vellum.

All processes of reproduction introduce small errors, especially now that different copying methods mean that the same drawing may be re-copied, or copies made in several different ways. Consequently, dimensions need to be written ('figured') on the drawing. The disclaimer 'Do not scale off dimensions' is commonly inscribed on architects drawings, to guard against errors arising in the copying process. Principal floor plans of the, Greenwich (UK).

Floor plan A is the most fundamental architectural, a view from above showing the arrangement of spaces in building in the same way as a, but showing the arrangement at a particular level of a building. Technically it is a horizontal section cut through a building (conventionally at four feet / one metre and twenty centimetres above floor level), showing walls, windows and door openings and other features at that level. The plan view includes anything that could be seen below that level: the floor, stairs (but only up to the plan level), fittings and sometimes furniture. Objects above the plan level (e.g. Beams overhead) can be indicated as dashed lines. Geometrically, is defined as a vertical of an object on to a horizontal plane, with the horizontal plane cutting through the building.

Site plan A is a specific type of plan, showing the whole context of a building or group of buildings. A site plan shows property boundaries and means of access to the site, and nearby structures if they are relevant to the design. For a on an urban site, the site plan may need to show adjoining streets to demonstrate how the design fits into the urban fabric.

Within the site boundary, the site plan gives an overview of the entire scope of work. It shows the buildings (if any) already existing and those that are proposed, usually as a building footprint; roads, parking lots, footpaths, trees and planting. For a construction project, the site plan also needs to show all the services connections: drainage and sewer lines, water supply, electrical and communications cables, exterior lighting etc. Site plans are commonly used to a building proposal prior to detailed design: drawing up a site plan is a tool for deciding both the site layout and the size and orientation of proposed new buildings. A site plan is used to verify that a proposal complies with local development codes, including restrictions on historical sites.

In this context the site plan forms part of a legal agreement, and there may be a requirement for it to be drawn up by a licensed professional: architect, engineer, landscape architect or land surveyor. Section drawing of the at Potsdam. Cross section A, also simply called a section, represents a vertical plane cut through the object, in the same way as a is a horizontal section viewed from the top. In the section view, everything cut by the section plane is shown as a bold line, often with a solid fill to show objects that are cut through, and anything seen beyond generally shown in a thinner line. Sections are used to describe the relationship between different levels of a building.

In the Observatorium drawing illustrated here, the section shows the dome which can be seen from the outside, a second dome that can only be seen inside the building, and the way the space between the two accommodates a large astronomical telescope: relationships that would be difficult to understand from plans alone. A sectional elevation is a combination of a cross section, with elevations of other parts of the building seen beyond the section plane. Geometrically, a cross section is a horizontal orthographic projection of a building on to a vertical plane, with the vertical plane cutting through the building. Isometric and axonometric projections Isometric and axonometric projections are a simple way of representing a three dimensional object, keeping the elements to scale and showing the relationship between several sides of the same object, so that the complexities of a shape can be clearly understood. There is some confusion about the terms isometric and axonometric. “Axonometric is a word that has been used by architects for hundreds of years.

Engineers use the word axonometric as a generic term to include isometric, diametric and trimetric drawings.” This article uses the terms in the architecture-specific sense. Despite fairly complex geometrical explanations, for the purposes of practical draughting the difference between isometric and axonometric is simple (see diagram above). In both, the plan is drawn on a skewed or rotated grid, and the verticals are projected vertically on the page. All lines are drawn to scale so that relationships between elements are accurate.

In many cases a different scale is required for different, and again this can be calculated but in practice was often simply estimated by eye. An uses a plan grid at 30 degrees from the horizontal in both directions, which distorts the plan shape.

Isometric graph paper can be used to construct this kind of drawing. This view is useful to explain construction details (e.g. Three dimensional joints in joinery).

The isometric was the standard view until the mid twentieth century, remaining popular until the 1970s, especially for textbook diagrams and illustrations. is similar, but only one axis is skewed, the others being horizontal and vertical. Originally used in cabinet making, the advantage is that a principal side (e.g. A cabinet front) is displayed without distortion, so only the less important sides are skewed. The lines leading away from the eye are drawn at a reduced scale to lessen the degree of distortion. The cabinet projection is seen in Victorian engraved advertisements and architectural textbooks, but has virtually disappeared from general use. An uses a 45 degree plan grid, which keeps the original orthogonal geometry of the plan.

The great advantage of this view for architecture is that the draughtsman can work directly from a plan, without having to reconstruct it on a skewed grid. In theory the plan should be set at 45 degrees, but this introduces confusing coincidences where opposite corners align. Unwanted effects can be avoided by rotating the plan while still projecting vertically. This is sometimes called a planometric or plan oblique view, and allows freedom to choose any suitable angle to present the most useful view of an object.

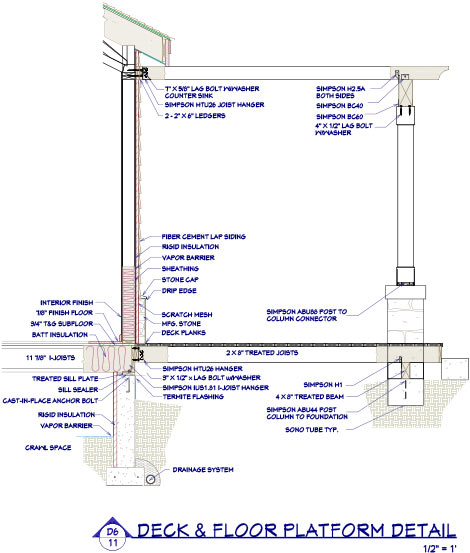

Traditional draughting techniques used 30-60 and 45 degree, and that determined the angles used in these views. Once the adjustable square became common those limitations were lifted. The axonometric gained in popularity in the twentieth century, not just as a convenient diagram but as a formal presentation technique, adopted in particular by the. Axonometric drawings feature prominently in the influential 1970's drawings of, and others, using not only straightforward views but worms-eye view, unusually and exaggerated rotations of the plan, and exploded elements. The axonometric view is not readily generated by CAD programmes which create views from a three dimensional model. Consequently, it is now rarely used. Detail drawings Detail drawings show a small part of the construction at a larger scale, to show how the component parts fit together.

They are also used to show small surface details, for example decorative elements. Section drawings at large scale are a standard way of showing building construction details, typically showing complex junctions (such as floor to wall junction, window openings, eaves and roof apex) that cannot be clearly shown on a drawing that includes the full height of the building. A full set of construction details needs to show plan details as well as vertical section details. One detail is seldom produced in isolation: a set of details shows the information needed to understand the construction in three dimensions. Typical scales for details are 1/10, 1/5 and full size.

In traditional construction, many details were so fully standardised, that few detail drawings were required to construct a building. For example, the construction of a would be left to the carpenter, who would fully understand what was required, but unique decorative details of the facade would be drawn up in detail. In contrast, modern buildings need to be fully detailed because of the proliferation of different products, methods and possible solutions.

Architectural perspective. Two point perspective, interior of Dercy House by, 1777. In drawing is an approximate representation on a flat surface of an image as it is perceived by the eye. The key concepts here are:.

Perspective is the view from a particular fixed viewpoint. Horizontal and vertical edges in the object are represented by horizontals and verticals in the drawing. Lines leading away into the distance appear to converge at a. All horizontals converge to a point on the, which is a horizontal line at eye level. Verticals converge to a point either above or below the horizon. The basic categorization of artificial perspective is by the number of vanishing points:.

where objects facing the viewer are orthogonal, and receding lines converge to a single vanishing point. reduces distortion by viewing objects at an angle, with all the horizontal lines receding to one of two vanishing points, both located on the horizon. introduces additional realism by making the verticals recede to a third vanishing point, which is above or below depending upon whether the view is seen from above or below. The normal convention in architectural perspective is to use two-point perspective, with all the verticals drawn as verticals on the page.

04 Masonry

Three-point perspective gives a casual, photographic snapshot effect. In professional, conversely, a or a is used to eliminate the third vanishing point, so that all the verticals are vertical on the photograph, as with the perspective convention.

This can also be done by digital manipulation of a photograph taken with a standard lens. Is a technique in painting, for indicating distance by approximating the effect of the atmosphere on distant objects.

03 Concrete

In daylight, as an ordinary object gets further from the eye, its contrast with the background is reduced, its colour saturation is reduced, and its colour becomes more blue. Not to be confused with or bird's eye view, which is the view as seen (or imagined) from a high vantage point.

Architectural Cad Details

In J M Gandy's perspective of the Bank of England (see illustration at the beginning of this article), Gandy portrayed the building as a picturesque ruin in order to show the internal plan arrangement, a precursor of the cutaway view. A image is produced by superimposing a perspective image of a building on to a photographic background. Care is needed to record the position from which the photograph was taken, and to generate the perspective using the same viewpoint. This technique is popular in computer visualisation, where the building can be rendered, and the final image is intended to be almost indistinguishable from a photograph.

Sketches and diagrams. Architect at his drawing board, 1893 Until the latter part of the twentieth century, all architectural drawings were manually produced, either by architects or by trained (but less skilled) (or ), who did not generate the design, although they made many of the less important decisions. This system continues with CAD draughting: many design architects have little or no knowledge of CAD software programmes and rely upon others to take their designs beyond the sketch stage. Draughtsmen may specialize in a type of structure, such as residential or commercial, or in a type of construction: timber frame, reinforced concrete, prefabrication etc.

The traditional tools of the architect were the or draughting table, and, and of different types. Drawings were made on, coated, and on. Would either be done by hand, mechanically using a, or a combination of the two.

Ink lines were drawn with a, a relatively sophisticated device similar to a dip-in pen but with adjustable line width, capable of producing a very fine controlled line width. Ink pens had to be dipped into ink frequently. Draughtsmen worked standing up, and kept the ink on a separate table to avoid spilling ink on the drawing. Twentieth century developments include the drawing board, and more complicated improvements on the basic T-square. The development of reliable allowed for faster draughting and stencilled lettering. Dry transfer lettering and half-tone sheets were popular from the 1970s until computers made those processes obsolete.

CGI & Computer-aided design. Computer generated perspective of the Moscow School of Management, by David Adjaye is the use of computer software to create drawings. Today the vast majority of technical drawings of all kinds are made using CAD.

Instead of drawing lines on paper, the computer records equivalent information electronically. There are many advantages to this system: repetition is reduced because complex elements can be copied, duplicated and stored for re-use. Errors can be deleted, and the speed of draughting allows many permutations to be tried before the design is finalised. On the other hand, CAD drawing encourages a proliferation of detail and increased expectations of accuracy, aspects which reduce the efficiency originally expected from the move to computerisation. Professional CAD software such as is complex and requires both training and experience before the operator becomes fully productive. Consequently, skilled CAD operators are often divorced from the design process. Simpler software such as and allows for more intuitive drawing and is intended as a design tool.

CAD is used to create all kinds of drawings, from working drawings to perspective views. (also called visualisations) are made by creating a three-dimensional model using CAD.

The model can be viewed from any direction to find the most useful viewpoints. Different software (for example ) is then used to apply colour and texture to surfaces, and to represent shadows and reflections. The result can be accurately combined with photographic elements: people, cars, background landscape. (BIM) is the logical development of CAD drawing, a relatively new technology but fast becoming mainstream. The design team collaborates to create a three-dimensional computer model, and all plans and other two-dimensional views are generated directly from the model, ensuring spatial consistency. The key innovation here is to share the model via the internet, so that all the design functions (site survey, architecture, structure and services) can be integrated into a single model, or as a series of models associated with each specialism that are shared throughout the design development process.

Some form of management, not necessarily by the architect, needs to be in place to resolve conflicting priorities. The starting point of BIM is spatial design, but it also enables components to be quantified and scheduled directly from the information embedded in the model.

An is a short film showing how a proposed building will look: the moving image makes three-dimensional forms much easier to understand. An animation is generated from a series of hundreds or even thousands of still images, each made in the same way as an architectural visualisation. A computer-generated building is created using a CAD programme, and that is used to create more or less realistic views from a sequence of viewpoints. The simplest animations use a moving viewpoint, while more complex animations can include moving objects: people, vehicles and so on. Architectural reprographics. Blueprint Reprographics or reprography covers a variety of technologies, media, and support services used to make multiple copies of original drawings.

Prints of architectural drawings are still sometimes called, after one of the early processes which produced a white line on blue paper. The process was superseded by the dye-line print system which prints black on white coated paper. The standard modern processes are the, and, of which the ink-jet and laser printers are commonly used for large-format printing. Although colour printing is now commonplace, it remains expensive above A3 size, and architect's working drawings still tend to adhere to the black and white / greyscale aesthetic. See also Wikimedia Commons has media related to.

Bertoline et al. (2002) Technical Graphics Communication. David Byrnes, AutoCAD 2008 For Dummies. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons; illustrated edition (4 May 2007). January 2, 2014, at the.

Local authorities worldwide publish similar information. Ching, Frank (1985), Architectural Graphics - Second Edition, New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold,. ^ Alan Piper, Drawing for Designers. Laurence King Publishing 2007. Page 57, definition of axonometric drawing.

^ W. McKay: McKay's Building Construction. Donhead Publishing 2005. A new reprint of the combined three volumes that McKay published between 1938 and 1944. Heavily illustrated textbook of architectural detailing.

July 10, 2011, at the. ^ Arthur Thompson, Architectural Design Procedures, Second Edition. Architectural Press: Elsevier 2007. Thomas W Schaller, Architecture in Watercolour.

Van Nostrand Re9inhold, New York 1990. The Great Perspectivists, by Gavin Stamp. RIBA Drawings Series, published by Trefoil Books London 1982. Richard Boland and Fred Collopy (2004).

Managing as designing. Corbusier's sketch design for his Cabanon. ^ Rendow Yee (2002). Architectural Drawing: A Visual Compendium of Types and Methods. Ellen Yi-Luen Do†& Mark D. Gross (2001). In: Artificial Intelligence Review 15: 135-149, 2001.

Papadakis (1988). Deconstruction in Architecture: In Architecture and Urbanism. Dated: 18 December 2007. Accessed: 24 September 2008.