Boeing Safety Program Model

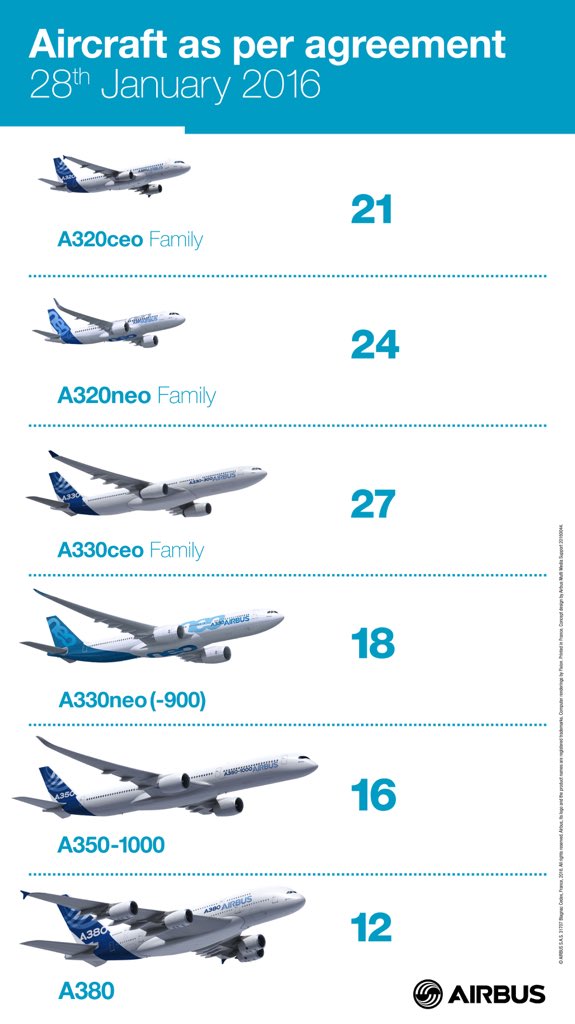

A and at The competition between and has been characterised as a in the large market since the 1990s. This resulted from a series of mergers within the global, with beginning as a European while the American absorbed its former arch-rival, in a 1997 merger. Other manufacturers, such as, and in the, and and in, were no longer in a position to compete effectively and withdrew from this market. In the 10 years from 2007 to 2016, Airbus has received 9,985 orders while delivering 5,644, and Boeing has received 8,978 orders while delivering 5,718. In the midst of their intense competition, each company regularly accuses the other of receiving unfair from their respective governments. United Airlines Airbus A320 and Boeing 737-900 on final approach In terms of sales, while the outsold the since its introduction in 1988, it is still lagging overall with 7,033 orders against 7,940 in January 2016.

Airbus received 4,471 orders since the launch in December 2010, while the got 3,072 from August 2011 till January 2016. In the same timeframe, the neo had 3,355 orders.

Boeing Regional Aviation Safety Initiatives 3. * Continued Operational Safety Program Operator reports Multi-Operator Message Issue classification (safety decision).

Through August, Airbus have a 59.4% market share of the re-engined single aisle market, while Boeing had 40.6%; Boeing has doubts on over-ordered A320 neos by new operators and expects to narrow the gap with replacements not already ordered. In July 2017, Airbus still had sold 1,350 more A320neos than Boeing had sold 737 MAXs.

In terms of deliveries, Boeing has shipped 9,522 aircraft of the 737 family since late 1967, with 8,016 of those deliveries since March 1, 1988, and has a further 4,430 on firm order as of May 2017. In comparison, has delivered 7,610 A320 series aircraft since their certification/first delivery in early 1988, with another 5,501 on firm order (as of May 2017). Cross-section comparison of the Airbus A380 (full length double deck) and the front section of Boeing 747-400 (only the front section has double deck) During the 1990s both companies researched the feasibility of a passenger aircraft larger than the, which was then the largest airliner in operation. Airbus subsequently launched a full-length, the, a decade later while Boeing decided the project would not be commercially viable and developed the third generation 747,instead. The Airbus A380 and the Boeing 747-8 are therefore placed in direct competition on long-haul routes. Rival performance claims by Airbus and Boeing appear to be contradictory, their methodologies unclear and neither are validated by a third party source. Boeing claims the 747-8I to be over 10% lighter per seat and have 11% less fuel consumption per passenger, with a trip-cost reduction of 21% and a seat-mile cost reduction of more than 6%, compared to the A380.

The 747-8F's empty weight is expected to be 80 tonnes (88 tons) lighter and 24% lower fuel burnt per ton with 21% lower trip costs and 23% lower ton-mile costs than the A380F. On the other hand, Airbus claims the A380 to have 8% less fuel consumption per passenger than the 747-8I and in 2007 Singapore Airlines CEO Chew Choong Seng stated the A380 was performing better than both the airline and Airbus had anticipated, burning 20% less fuel per passenger than the airline's fleet.

Emirates' also claims that the A380 is more fuel economic at Mach 0.86 than at 0.83. One independent, industry analysis shows fuel consumption in litres per seat per 100 kilometres flown (L/seat/100 km) as 3.27 for the A380 and 3.35 for the B747-8I, or a fuel cost per seat mile of $0.055 and $0.057 respectively.

– A possible, as yet uncommitted, re-engined A380neo is expected to achieve 2.82 or 2.65 L/seat/100 km depending on the options taken. Airbus emphasises the longer range of the A380 while using up to 17% shorter runways. The A380-800 has 478 square metres (5,145.1 sq ft) of cabin floor space, 49% more than the 747-8, while commentators noted the 'downright eerie' lack of engine noise, with the A380 being 50% quieter than a 747-400 on takeoff.

Airbus delivered the 100th A380 on 14 March 2013. From 2012, Airbus will offer, as an option, a variant with improved maximum take-off weight allowing for better payload/range performance. The precise increase in maximum take-off weight is still unknown. British Airways and Emirates will be the first customers to take this offer. As of December 2015, Airbus has 319 for the passenger version of the A380 and is not currently offering the. Production of the A380F has been suspended until the A380 production lines have settled with no firm availability date. A number of original A380F orders were cancelled following in October 2006, notably and the.

Some A380 launch customers converted their A380F orders to the passenger version or switched to the 747-8F or 777F aircraft. At Farnborough in July 2016, Airbus announced that in a 'prudent, proactive step,' starting in 2018 it expects to deliver 12 A380 aircraft per year, down from 27 deliveries in 2015. The firm also warned production might slip back into red ink on each aircraft produced at that time, though it anticipates production will remain in the black for 2016 and 2017. The firm expects that healthy demand for its other aircraft would allow it to avoid job losses from the cuts. As of June 2014, Boeing has 51 for the 747-8I passenger version and 69 for the 747-8F freighter.

EADS/Northrop Grumman KC-45A vs Boeing KC-767. Main article: The announcement in March 2008 that Boeing had lost a US$40 billion refuelling aircraft contract to Northrop Grumman and Airbus for the with the drew angry protests in the. Upon review of Boeing's protest, the ruled in favour of Boeing and ordered the USAF to recompete the contract.

Later, the entire call for aircraft was rescheduled, then cancelled, with a new call decided upon in March 2010 as a. Boeing later won the contest against Airbus (Northrop having withdrawn) and US Aerospace/Antonov (disqualified), with a lower price, on February 24, 2011. The price was so low some in the media believe Boeing would take a loss on the deal; they also speculated that the company could perhaps break even with maintenance and spare parts contracts. In July 2011, it was revealed that projected development costs rose $1.4bn and will exceed the $4.9bn contract cap by $300m. For the first $1bn increase (from the award price to the cap), the U.S. Government would be responsible for $600m under a 60/40 government/Boeing split. With Boeing being wholly responsible for the additional $300m ceiling breach, Boeing would be responsible for a total of $700m of the additional cost.

Regional jets Neither Boeing nor Airbus is directly present in the regional jet market. However, in October 2017 Airbus took a 50.01% stake in 's programme, while in December 2017 Boeing confirmed that it was holding discussions with, whose range directly competes with the Cseries. Modes of competition Outsourcing Because many of the world's airlines are wholly or partially government owned, aircraft procurement decisions are often taken according to political criteria in addition to commercial ones. Boeing and Airbus seek to exploit this by subcontracting production of aircraft components or assemblies to manufacturers in countries of strategic importance in order to gain a competitive advantage overall. For example, Boeing has maintained longstanding relationships since 1974 with Japanese suppliers including and by which these companies have had increasing involvement on successive Boeing jet programs, a process which has helped Boeing achieve almost total dominance of the Japanese market for commercial jets.

Outsourcing was extended on the 787 to the extent that Boeing's own involvement was reduced to little more than project management, design, assembly and test operation, outsourcing most of the actual manufacturing all around the world. Boeing has since stated that it 'outsourced too much' and that future airplane projects will depend far more on its own engineering and production personnel.

Partly because of its origins as a consortium of European companies, Airbus has had fewer opportunities to outsource significant parts of its production beyond its own European plants. However, in 2009 Airbus opened an assembly plant in, for production of its A320 series airliners. Technology Airbus sought to compete with the well-established Boeing in the 1970s through its introduction of advanced technology. For example, the made the most extensive use of yet seen in an aircraft of that era, and by automating the functions, was the first jet to have a two-man flight crew. In the 1980s Airbus was the first to introduce digital controls into an airliner (the ).

With Airbus now an established competitor to Boeing, both companies use advanced technology to seek performance advantages in their products. Many of these improvements are about weight reduction and fuel efficiency. For example, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is the first large airliner to use 50% composites for its construction.

The features 53% composites. Provision of engine choices The competitive strength in the market of any airliner is considerably influenced by the choice of engine available.

In general, airlines prefer to have a choice of at least two engines from the major manufacturers, and. However, engine manufacturers prefer to be single source, and often succeed in striking commercial deals with Boeing and Airbus to achieve this. Several notable aircraft have only provided a single engine offering: the series onwards , the , the , the , and the Boeing /200LR/F. However, the Airbus A380 has a choice of either the or the, while the Boeing 787 Dreamliner can be fitted with the or the.

As of the late 2000s, there appears to be a polarizing of both the engine suppliers as well as the airline manufacturers, such as Boeing and General Electric partnering for the upcoming, and Airbus working closely with Rolls Royce for the. Currency and exchange rates Boeing's production costs are mostly in, whereas Airbus's production costs are mostly in. When the dollar appreciates against the euro the cost of producing a Boeing aircraft rises relatively to the cost of producing an Airbus aircraft, and conversely when the dollar falls relative to the euro it is an advantage for Boeing. There are also possible currency risks and benefits involved in the way aircraft are sold. Boeing typically prices its aircraft only in dollars, while Airbus, although pricing most aircraft sales in dollars, has been known to be more flexible and has priced some aircraft sales in Asia and the Middle East in multiple currencies.

Depending on currency fluctuations between the acceptance of the order and the delivery of the aircraft this can result in an extra profit or extra expense—or, if Airbus has purchased insurance against such fluctuations, an additional cost regardless. Safety and quality Both aircraft manufacturers have good safety records on recently manufactured aircraft and generally, both firms have a positive reputation of delivering well-engineered and high-quality products. By convention, both companies tend to avoid safety comparisons when selling their aircraft to airlines or comparisons on product quality. Most aircraft dominating the companies' current sales, the and families and both companies' offerings, have good safety records. Older model aircraft such as the, -100/-200, -100/SP/200/300, and, which were respectively first flown during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, have had higher rates of fatal accidents.

According to Airbus's, the will not cause customers to switch airplane suppliers. Aircraft prices Airbus and Boeing publish list prices for their aircraft but the actual prices charged to vary; they can be difficult to determine and tend to be much lower than the list prices. Both manufacturers are engaged in a to defend their. The actual transaction prices may be as much as 63% less than the list prices, as reported in 2012 in the, giving some examples from the subsidiary Ascend: Model List price 2012, US$M Market price% Discount -800 84 41 51% -900ER 90 45 50% -300ER 298 149 50% 81 30 63% 88 40 55% -200 209 84 60% In May 2013, magazine reported that the offered at $225 million was selling at an average of $116m, a 48% discount. For Ascend's Les Weal, Launch customers obtain good prices on heavier aircraft, Lessors are large buyers and benefit too, like airlines as or since their name gives credibility to a program. In its annual report, cites a €149 million ($195 million) A380, a 52% cut, while in an October 2011 financial release notes a $234 million for its A380 to. Teal group's notes that Boeing's for the was better when it was alone in its long-haul, large capacity twinjet market but this advantage dissipates with the coming.

For Leeham's Scott Hamilton, small orders are content with 35-40% discount but large airlines sometimes attain 60% and customers with old ties with Boeing like, or get a guaranteeing them no other customer gets a lower price. Indicates Southwest, the largest 737 customer with 577, got a unit price of $34,7 million for its 737 MAX order of 150 in December 2011, a 64% discount. Got 53% in September 2001 and claims to obtain at least the same on its last 175 orders. The Airbus-Boeing indicates got a $19,4 million unit price on its A319 order for 120 in 2002, a 56% discount at the time, the same kind of rebate got for its A320 order of 234 on 18 March 2013. Each sale include an covering the workforce and raw material costs increases and as acquisition cost represents 15% of the 20 year, discussions also include the delivery date, guarantees, financial incentives, maintenance and training.

At Airbus, final price in large campaigns is validated by a committee comprising sales head, program director, financial principal and CEO who has the final cut. The compete with the (both pictured) and the Subsidies Boeing has continually protested over launch aid in the form of credits to Airbus, while Airbus has argued that Boeing receives illegal subsidies through military and research contracts and tax breaks. In July 2004, (then CEO of Boeing) accused Airbus of abusing a 1992 bilateral EU-US agreement regarding large civil aircraft support from governments. Airbus is given reimbursable launch investment (RLI, called 'launch aid' by the US) from European governments with the money being paid back with interest, plus indefinite royalties if the aircraft is a commercial success. Airbus contends that this system is fully compliant with the 1992 agreement and rules. The agreement allows up to 33 per cent of the program cost to be met through government loans which are to be fully repaid within 17 years with interest and royalties. These loans are held at a minimum interest rate equal to the cost of government borrowing plus 0.25%, which would be below market rates available to Airbus without government support.

Airbus claims that since the signing of the EU-U.S. Agreement in 1992, it has repaid European governments more than U.S.$6.7 billion and that this is 40% more than it has received.

Airbus argues that military contracts awarded to Boeing (the second largest U.S. Defence contractor) are in effect a form of subsidy (see the vs EADS (Airbus) military contracting controversy). Government support of technology development via also provides support to Boeing.

In its recent products such as the 787, Boeing has also received support from local and state governments. Airbus's parent, itself is a military contractor, and is paid to develop and build projects such as the transport and various other military aircraft.

In January 2005, European Union and United States trade representatives and agreed to talks aimed at resolving the increasing tensions. These talks were not successful, with the dispute becoming more acrimonious rather than approaching a settlement. World Trade Organization litigation. 'We remain united in our determination that this dispute shall not affect our cooperation on wider bilateral and multilateral trade issues. We have worked together well so far, and intend to continue to do so.' Joint EU-US statement On 31 May 2005 the filed a case against the for providing allegedly illegal subsidies to Airbus.

Twenty-four hours later the European Union filed a complaint against the United States protesting support for Boeing. Increased tensions, due to the support for the Airbus A380, escalated toward a potential trade war as the launch of the neared. Airbus preferred the A350 program to be launched with the help of state loans covering a third of the development costs, although it stated it will launch without these loans if required. The A350 will compete with Boeing's most successful project in recent years, the. EU trade officials questioned the nature of the funding provided by NASA, the, and in particular the form of R&D contracts that benefit Boeing; as well as funding from US states such as Washington, Kansas, and Illinois, for the development and launch of Boeing aircraft, in particular the 787.

An interim report of the investigation into the claims made by both sides was made in September 2009. In September 2009, the and reported that the World Trade Organization would likely rule against Airbus on most, but not all, of Boeing's complaints; the practical effect of this ruling would likely be blunted by the large number of international partners engaged by both plane makers, as well as the expected delay of several years of appeals.

For example, 35% of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is manufactured in. Thus, some experts are advocating a negotiated settlement.

In addition, the heavy government subsidies offered to automobile manufacturers in the United States have changed the political environment; the subsidies offered to and dwarf the amounts involved in the Airbus-Boeing dispute. In March 2010, the WTO ruled that European governments unfairly financed Airbus. In September 2010, a preliminary report of the WTO found unfair Boeing payments broke WTO rules and should be withdrawn.

In two separate findings issued in May 2011, the WTO found, firstly, that the US defence budget and NASA research grants could not be used as vehicles to subsidise the civilian aerospace industry and that Boeing must repay $5.3 billion of illegal subsidies. Secondly, the WTO partly overturned an earlier ruling that European Government launch aid constituted unfair subsidy, agreeing with the point of principle that the support was not aimed at boosting exports and some forms of public-private partnership could continue. Part of the $18bn in low interest loans received would have to be repaid eventually; however, there was no immediate need for it to be repaid and the exact value to be repaid would be set at a future date. Both parties claimed victory in what was the world's largest trade dispute. On 1 December 2011 Airbus reported that it had fulfilled its obligations under the WTO findings and called upon Boeing to do likewise in the coming year. The United States did not agree and had already begun complaint procedures prior to December, stating the EU had failed to comply with the 's recommendations and rulings, and requesting authorisation by the DSB to take countermeasures under Article 22 of the DSU and Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union requested the matter be referred to arbitration under Article 22.6 of the DSU.

The DSB agreed that the matter raised by the European Union in its statement at that meeting be referred to arbitration as required by Article 22.6 of the DSU however on 19 January 2012 the US and EU jointly agreed to withdraw their request for arbitration. On 12 March 2012 the appellate body of the WTO released its findings confirming the illegality of subsidies to Boeing whilst confirming the legality of repayable loans made to Airbus. The WTO stated that Boeing had received at least $5.3 billion in illegal cash subsidies at an estimated cost to Airbus of $45 billion. A further $2 billion in state and local subsidies that Boeing is set to receive have also been declared illegal.

Boeing and the US government were given six months to change the way government support for Boeing is handled. At the DSB meeting on 13 April 2012, the United States informed the DSB that it intended to implement the DSB recommendations and rulings in a manner that respects its WTO obligations and within the time-frame established in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement. The European Union welcomed the US intention and noted that the 6-month period stipulated in Article 7.9 of the SCM Agreement would expire on 23 September 2012. On 24 April 2012, the European Union and the United States informed the DSB of Agreed Procedures under Articles 21 and 22 of the DSU and Article 7 of the SCM Agreement. On 25 September 2012 the EU requested discussions with the USA, because of the alleged non compliance of the US and Boeing with the WTO ruling of 12 March 2012. On 27 September 2012 the EU requested the WTO to approve EU countermeasures against USA's subsidy of Boeing.

The WTO approved creating a panel to rule on the disputed compliance this was initially to rule in 2014 but is not now expected to complete its work before 2016 due to the complexity of the case. The EU wants permission to place trade sanctions of up to 12 billion US$ annually against the USA. The EU believes this amount represents the damage the illegal subsidies of Boeing cause to the EU. On 19 December 2014 the EU requested WTO mediated consultations with the US over the tax incentives given by the state of Washington to large civil aircraft manufacturers which they believed violated the earlier WTO ruling, on 22 April 2015 at the request of the EU a WTO panel was set up to rule on the complaint. The tax incentives given by the state of Washington and believed to be the largest in US history surpassing the previous record of $5.6bn over 30 years awarded by the state of New York to the aluminum producer Alcoa in 2007. Airlines Industry Profile: United States, Datamonitor, November 2008, pp.

13–14. ^ (PDF). ^ (Press release). 15 January 2018. Flight Global. 16 August 2016.

February 20, 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Flight Global. Flight Global.

13 October 2016. Flight Global. CAPA - Centre for Aviation. 18 January 2016.

CAPA - Centre for Aviation. 15 October 2015. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

January 27, 2016. Sep 22, 2016. Addison Schonland (July 10, 2017). May 31, 2017.

Retrieved June 14, 2017. Archived from on December 30, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

January 2010. Archived from (Microsoft Excel) on December 23, 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2012. December 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

David Kaminski Morrow (6 Nov 2017). Los Angeles Times. 10 July 1995. Retrieved 30 December 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-21. 13 December 2007.

Archived from on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007. Flottau, Jens (21 November 2012). Retrieved 22 November 2012. Clark points out that 'the faster you fly the A380, the more fuel-efficient she gets; when you fly at Mach 0.86 she is better than at 0.83.' Retrieved 2014-06-29.

Retrieved 2012-02-08. Saporito, Bill (23 November 2009). TIME magazine. From the original on 19 September 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2010. 2016-03-03 at the. Airbus, 14 March 2013.

Retrieved 2011-05-21. Retrieved 22 November 2015. Quentin Wilber, Dell (8 November 2006). The Washington Post.

Boeing Safety

Retrieved 30 December 2011. Robertson, David., 3 October 2006. Schwartz, Nelson D., CNN, 1 March 2007. Clark, Nicola (12 July 2016). Retrieved 13 January 2018. Wall, Robert; Ostrower, Jon (12 July 2016).

Retrieved 13 January 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2014. Retrieved 2011-05-21. Defense Industry Daily. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Leeham News and Comment: 2011-07-17 at the., 12-7-2011, visited: 3-2-2012. Broken link:. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Defensenews.com:, 27-7-2011, visited: 3-2-2012. 'Airbus and Bombardier Announce C Series Partnership' (Press release).

16 October 2017.,. 'Boeing and Embraer Confirm Discussions on Potential Combination' (Press release). December 21, 2017.

And. Gates, Dominic (March 1, 2010). The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2010-06-16. October 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

Retrieved 28 September 2016. Thomas, Geoffrey (April 4, 2008). Retrieved 2008-11-08.

Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. October 30, 2009.

Muellerleile, Christopher M (2009). 'Financialization takes off at Boeing'. Journal of Economic Geography. Boeing’s engineers. tended to be first and foremost concerned with safety and quality.

This contributed to Boeing’s solid reputation. Gray, Edmund R.; Balmer, John MT (1998). Long Range Planning. Airbus. enjoys a high-profile image and positive reputation. (PDF). Robert Wall & Andrea Rothman (17 January 2013).

Retrieved 17 January 2013. I don't believe that anyone's going to switch from one airplane type to another because there's a maintenance issue,' Leahy said. 'Boeing will get this sorted out. TIM HEPHER (9 July 2012). DANIEL MICHAELS (9 July 2012).

Agustino Fontevecchia (21 May 2013). ^ Vincent Lamigeon (13 June 2013). Vinay Bhaskara (November 25, 2014). Airways News. Archived from on November 17, 2015. DAVID KAMINSKI-MORROW (24 December 2014). Flight Global.

(Press release). Leeham news and comment.

22 February 2016. 8 March 2016. (in French). 13 September 2016. May 16, 2016. Chris Bryant (Nov 13, 2017).

Arvai (January 19, 2018). Robertson, David (October 4, 2006). London: The Times Business News. Associated, The (2011-01-20). Retrieved 2013-02-16. Flight Global.

14 October 2016. Retrieved 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2014-02-06. ^ boeing.com.

Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Flight Global.

Retrieved 2014-02-06. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018. 14 August 2017.

Retrieved 13 January 2018. 14 August 2017. Kasper Oestergaard (January 26, 2018). Forecast International.

Retrieved 2011-01-09. O'Connell, Dominic; Porter, Andrew (29 May 2005). Archived from on 14 January 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

7 October 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2014. The Economist. 23 March 2005. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

Defense Aerospace. Retrieved 2010-01-02. Milmo, Dan (14 August 2009). London: The Guardian. 5 September 2009. Clark, Nicola (2009-09-03). Europe;United States: nytimes.com.

Retrieved 2011-05-21. Boeing Set for Victory Over Airbus in Illegal Subsidy Case, Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2009, p.A1. 3 March 2010.

Retrieved 2010-06-16. Paris: Reuters. 15 September 2010. Freedman, Jennifer M. Retrieved 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2011-05-21. Lewis, Barbara (2011-05-19).

Retrieved 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2011-05-21. Khimm, Suzy (2011-05-17). The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

Retrieved 2014-02-06. European Commission. Retrieved 2012-09-28. Retrieved 2012-09-28. Retrieved 13 January 2018. Reid Wilson (12 November 2013).

Washington Post. Jon Ostrower (10 December 2013). Bibliography. Newhouse, John (2007), Boeing versus Airbus, USA: Vintage Books, External links.